According to Chun and Evans (2018), continued white hegemonic practices in university and college administration and faculty have failed to develop a representative institutional culture and organizational structure that is responsive to the needs of diverse students and faculty. The purpose of this article is to discuss this issue, relate it to how the concept of culture is used in education from a critical perspective, and share with you a set of recommendations, activities, and strategies based on not only on research, but my direct personal experience as a minority faculty member and academic leader, and my interactions with other faculty and students who are culturally- and linguistically-diverse.

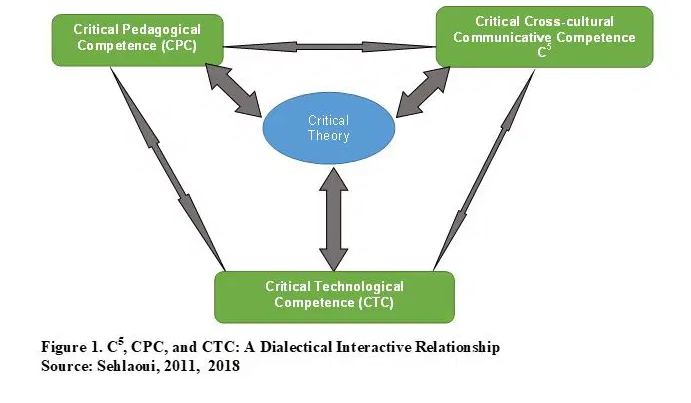

My recommendations and analysis of this issue are based on the fundamental concept of culture that is at the heart of what we do as human beings. The term culture is defined here within its socio-economic and political context and as part of such a context. It is viewed as a dynamic process in which individuals are in a constant struggle for representation and the need to have an authentic voice (e.g. Sehlaoui, 1999, 2011, 2018a; Giroux, 1992; Quantz, 1992). Figure 1 illustrates the fundamental role this critical view of culture plays and the interactive and dynamic relationship that exists between three complex competences with a focus on the critical cross-cultural communicative competence (C5) that is more relevant to our discussion of diversity and inclusion.

According to Sehlaoui (1999, 2011, 2018b), C5 is defined as our ability to effectively communicate across cultures and with diverse individuals, to create a representative administration that is responsive to the needs of diverse students and faculty. C5 involves respect, tolerance, critical understanding of various points of view while allowing culturally and linguistically diverse individuals to share power relations and have an authentic voice (Sehlaoui, 2011). It’s a view of a transformational leadership that empowers others.

Both systemic and individual factors contribute to our problematic situation. For example, Chun & Evans (2018), among others, document the fact that:

- Over the last decade many racist incidents occurred at colleges and universities.

- The hostile and divisive national political climate poses an obstacle in creating representative and culturally responsive higher education institutions today.

- Diversity is often used as a marketing tool to showcase an institution in a positive light, rather than given priority and incorporated in a systemic manner to become part of the institutions’ strategic plan.

At the systemic level, even when a minority faculty member has the ability to lead and possesses the qualities identified by researchers as it relates to leadership and success, the presence of stereotypes, racism, and biases often prevail over positive leadership characteristics that a minority individual holds (Chun & Evans, 2018; Gordon, 2000). This observation was corroborated to me as minority faculty and as an academic leader during my 32 years of experience in the field of education and through my interactions with other minority individuals who have made similar observations. Research has addressed these issues at the systemic level and the following is a brief description of some of the suggested strategies and recommendations.

Research-based recommendations for bringing change

Chun and Evans (2018) stress the need for a new leadership model “to reshape and replace hierarchical and elite modes of governance and build inclusive environments for diverse faculty, staff, administrators, and students” (p. 221). Other researchers also stress the need for bold and courageous leadership to overcome internal and external forces resisting diversity change (Allen, 2018; Clark, Fasching-Varner & Brimhall-Vargas, 2012).

Internal forces, according to Chun and Evans (2018), are created by what they describe as “continued dominance of white, male, heterosexual perspectives in university and college administration” (p. xiii). To overcome these hegemonic internal practices, these researchers, among others, call for the importance of devoting significant funding resources to diversity and inclusion initiatives and practices. They also emphasize new diverse and dynamic models of leadership that use strategies which aim at:

- Building teamwork

- Valuing cultural differences

- Creating trust-based rather than fear-based environments

- Using an administration system that is culturally responsive, representative, and powerful enough to bring about organizational change

Of course, as is the case with any challenge or problem, the first step is to recognize or identify the problem. The following statement was shared with me by a colleague at a state university: “I think our college is on target with diversity and inclusion. I don’t see any problem in that area. We invite culturally diverse individuals to apply for our faculty positions and we hire them. We also reach out to diverse student populations. We have a good percentage of diverse students and faculty.”

Statements like these illustrate a denial stage in the process of developing an authentic critical cross-cultural communication dialogue (Sehlaoui, 2011). As a result, institutions of higher education need to offer their academic leaders professional development opportunities to develop their C5. Many researchers have identified key features of successful diversity organizational learning programs. For example, Chun and Evans (2018) shared 20 strategies and recommendations based on their research. Other recommended research-based and system-related strategies include:

- Offering classes in cross-cultural communication competencies at the graduate and undergraduate levels and measuring impact after completion/graduation (Sehlaoui, 2011; 2018a). These courses focus on the critical view of cultural dynamics and move beyond the positivist, hegemonic, and traditional views of education.

- Creating centers for advocacy for critical cross-cultural and multicultural education and supporting them financially (Chun & Evans, 2018).

- Providing incentives for faculty and staff to seek training in organizational diversity and inclusion to develop their C5 (Wilson, 2018).

- Creating mentoring and supportive programs to encourage faculty from minority groups to hold decision-making positions and build structures of support to retain them (Norhafezah, Rosna, Nena & Aizan, 2018). It is not enough to hire a minority person to serve in a leadership position when the climate in such an institution may not be welcoming or supportive of diversity and inclusion.

- Finally, institutions of higher education should also support and engage their academic leaders in opportunities to genuinely engage in global educational programs, especially since our world is becoming more and more diverse.

Projected U.S. demographics

While there is need for systematic organizational learning to implement diversity culture change across campus (Chun & Evans, 2018; Saathoff, 2017), it should be noted that cultural change is a gradual process that is influenced by our nation’s ever-changing demographics (Stanley, Watson, Reyes & Varela, 2018). According to Goldstein, (2016), “census projections show that by the 2050 Census, the United States will no longer have a clear white majority—at least as we define ‘white’ today. Fifty-three percent of the population will be multiracial or nonwhite, compared with less than 40% currently”.

Researchers believe this racial shift will happen even if the federal government issues new restrictive immigration policies, because the growth of the nonwhite population is driven more by fertility than by immigration. These demographic changes are a reality and institutions of higher education need to adapt and be prepared to face the challenge by providing diverse and inclusive leadership styles and institutional cultures.

Promoting change: a critical incident process-oriented approach

Thus far we have looked at the lack of diversity and inclusion initiatives and practices in higher education from the systemic level; let us now consider it from the individual level and provide some recommendations for addressing the problem.

At the individual level, researchers in multilingual and multicultural education (e.g. Grant & Sleeter, 2011; Sehlaoui 1999, 2001, 2018a, 2018b), and others in the area of leadership as it relates to the issue of diversity and inclusion (e.g. Chun and Evans, 2018), have identified a number of key challenges:

- Power struggles where the more powerful people impose their agendas/interests on the less powerful individuals

- Lack of critical cross-cultural communicative competence among educators and academic leaders results in more conflicts that perpetuate the status-quo

- Ignorance breeds more fear and anxiety

- Lack of representation in curriculum and instruction as well as leadership leads to educational failure of individuals and financial losses for societies

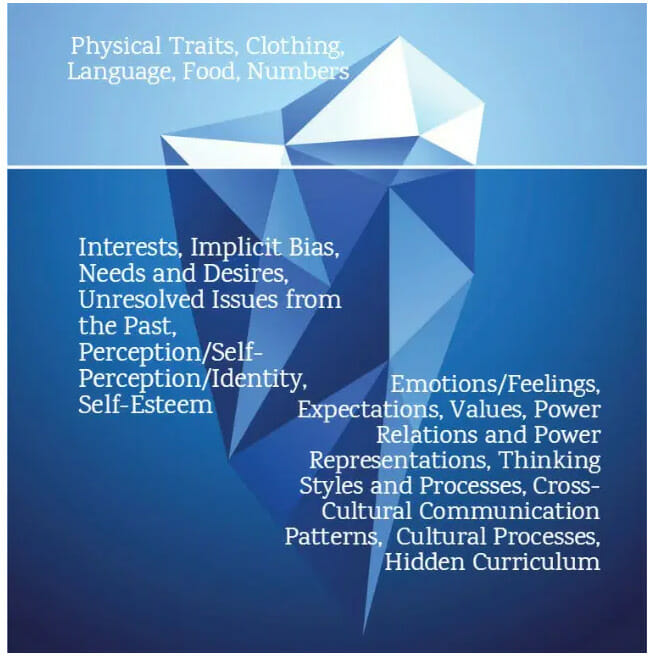

From this critical perspective, culture is seen as a site of struggle, a place where multiple interpretations come together, but where there is always a dominant force based on asymmetrical power relations that exist in each socio-economic and political context. Higher education institutions are examples of these contexts. Figure 2 illustrates that at the individual level, people tend to focus on the tip of the iceberg, which covers the physical traits and superficial facts and numbers/stats that may be misleading when it comes to issues of diversity and inclusion and the development of C5. The hidden part of the iceberg is what usually counts the most in terms of representation of diverse individuals in the power dynamics and decision-making processes of an institution.

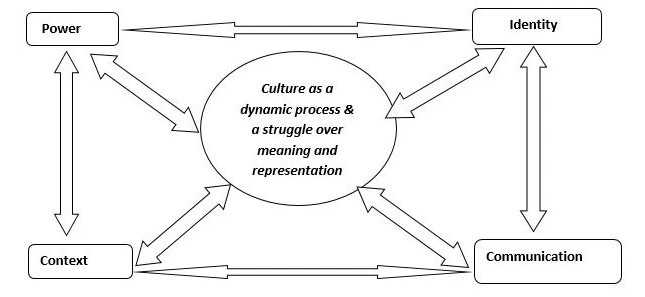

Critical theorists and pedagogues conclude that cross-cultural communication, including computer-mediated communication, cannot be understood without considering the power dynamics of relationships (Sehlaoui, 2011, 2018a). Understanding the power dynamics of a situation cannot be achieved in isolation. The dynamic nature of the concept of cultural identity is in an interactional relationship with the concepts of power, communication, context, and culture, with the latter concept being at the center of these interactional and dialectical relationships (see Figure 3).

Professional development activities that aim to address the issue of diversity and inclusion at the individual level should be based on a critical definition of culture and the processes involved in the development of C5 in key leadership personnel (Sehlaoui, 2018a; 2018b). The critical pedagogical approach advocated in this article recommends use of critical-incident professional development activities during which participants are faced with scenarios and situations where issues of diversity and inclusion are focused on from various viewpoints. Activities such as the following can be adapted from Sehlaoui (1999 and 2018b):

- Cross-cultural dialogues

- Case studies, critical incidents, and scenarios

- Matching exercise: The Stages of C5 Continuum

However, it should be emphasized that prior to engaging in such professional development activities, faculty and leaders must (1) recognize that there is a problem, (2) define the problem, (3) create a non-threatening climate for an authentic cross-cultural dialogue to take place, and (4) develop what Chun and Evans (2018) call “a sustained and deliberate institutional planning and action” (p. xvi).

Cross-cultural dialogue activity: In this activity, participants are invited to explore some cultural processes and patterns of communication, such as polychronic vs. mono-chronic, the process of stereotyping, and implicit bias, by having them act out the cross-cultural dialogues and discuss the cross-cultural communication issues that may contribute to reinforcing hegemonic practices at the individual level.

Case studies/critical incident/scenarios: In this activity, participants are invited to explore cases of implicit institutional bias and hegemonic practices while exploring the concept of hidden curriculum. The hidden curriculum is defined in critical pedagogy as being an implicit curriculum. Rather than coming about by design, it represents behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge that are communicated without conscious intent—it is an accumulation of values communicated indirectly, through actions and words that are part of everyday life in a community (Giroux, 1981 and 1992). Because it is hidden, it requires more attention and direct observation in educational settings. Participants in these exercises should study the concepts of hidden curriculum and implicit bias and share effective strategies on how to address them within their unique institutional context.

Matching exercise to assess the stages of C5 continuum: This assessment activity is adapted from Bennett’s (1993) ethno-relativist model. Participants are provided with statements related to diversity and inclusion that were anonymously collected from individuals. Based on these statements, participants work together to match the statements with the stages of the C5. The purpose is to raise awareness of these stages of development so as to create inclusive and culturally responsive leadership practices.

The goal of activities such as these is to develop in the participants the language of critique and the language of possibility. According to Giroux (1981), the language of critique is defined as the participants’ ability to defend their pedagogical decisions/practices in front of various audiences. It also refers to their ability to discover the hidden curriculum and to define, recognize, and document the existence of issues of diversity and inclusion in their institutions in a proactive way.

Qualitative methods of measuring diversity and inclusion progress

When it comes to assessing the progress being made in the area of diversity and inclusion in higher education, according to research (e.g. Chun & Evans, 2018; Taylor, Beck, Lahey & Froyd, 2017; Wolff et al., 2015), numbers and percentages of representation alone are meaningless unless we focus on measures of influence and power. For example, at any given institution, we should measure:

- Minority individuals’ titles and level within an institution of higher education to show how much relative power they have.

- How often minority individuals attend pivotal meetings and councils, or how much they are involved in key decision-making processes.

Other guiding questions in measuring diversity and inclusion practices may include:

- Who’s invited to a meeting or to participate in research, grant projects, committees? Who gets to speak and how often? Are we leaving out anyone whose input would be valuable?

- Have we created conditions where every person can contribute in their unique and meaningful way while feeling safe and secure by doing so? If not, do we have the courage to admit there is a problem and work together to change it?

- How much money do we invest in addressing issues of diversity and inclusion?

- Are we aware of how the norms, power structures, and inequities in society can easily become embedded in an institution? If so, what have we done about it?

These are just some examples of the types of questions that can be posed when trying to assess diversity and inclusion at our institutions. Because each institution is unique, the questions used to effectively guide the assessment process will vary.

Conclusion

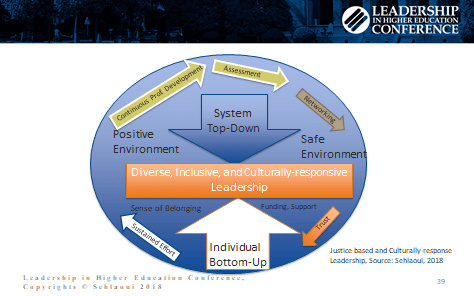

I will close this article with a slide from my presentation at the 2018 Leadership in Higher Education Conference. It illustrates necessary components for promoting culturally responsive campuses. To achieve this goal, institutions of higher education need to use both top-down and bottom-up processes and strategies for organizational cultural change that are based on trust, sustained efforts, moral and financial support, and the creation of a positive and safe environment. The need for continuous professional development and networking at the individual and institutional levels is necessary to facilitate and support such a change. On-going assessment of the effectiveness of the diversity and inclusion plan is cyclical in this model.

Abdelilah Salim Sehlaoui, EdD, is currently College of Education Grant Research Director/Professor of TESOL and Applied Linguistics at the School of Teaching and Learning, Sam Houston State University (SHSU). He also served as chair of Language, Literacy & Special Population Department at SHSU. He spoke on this topic at the 2018 Leadership in Higher Education Conference.

References

Allen, S. (2018). Creative Diversity: Promoting Interculturality in Australian Pathways to Higher Education. Journal of International Students, 8(1), 251-273.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Chun, E. & Evans, A. (2018). Leading a diversity culture shift in higher education: Comprehensive organizational learning strategies. New York, NY: Routledge

Clark, C., Fasching-Varner, K. J., & Brimhall-Vargas, M. (2012). Occupying the Academy: Just how Important is Diversity Work in Higher Education? Rowman & Littlefield.

Giroux, H. A. (1981). Ideology, culture and the process of schooling. Barcombe, England: Falmer Press.

Giroux, H. (1992). Critical literacy and student experience: Donald Graves’ approach to literacy. In P.

Shannon (Ed.). Becoming political: Readings and writings in the politics of education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann

Goldstein, D. (2016). America: This Is Your Future, What’s the country really going to look like in 30 years? Get ready for older, more diverse, and new tensions about who gets what. Retrieved January 12, 2019 from: https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2016/11/political-future-of-america-generations-diversity-tensions-000235

Grant, C. & Sleeter, C. E. (2011). Doing multicultural education for achievement and equity. New York, NY: Routledge.

Norhafezah, Y., Rosna A. H., Nena P. V., & Aizan, Y. (2018). Managing diversity in higher education: A strategic communication approach. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication. 28(1), 41-60.

Quantz, R. A. (1992). On critical ethnography (with some postmodern considerations). In M. D. LeCompte, W. L. Millroy, and J. Preissle (Eds.). The handbook of qualitative research in education. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Saathoff, S. D. (2017). Healing Systemic Fragmentation in Education Through Multicultural Education. Multicultural Education, 25(1), 2-8.

Sehlaoui, A. S. (2001). Developing Cross-cultural Communicative Competence in Preservice ESL/EFL Teachers: A Critical Perspective. Language, Culture, and Curriculum Journal, Vol. 14:1, 2001

Sehlaoui, A. S. (1999). Developing cross-cultural communicative competence in ESL/EFL preservice teachers: A critical perspective. (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 1999). Dissertation Abstracts International, DAI-A 60/06, p. 2042, Publication # 99348338.

Sehlaoui, A. S. (2011). Developing ESL/EFL Teachers’ Cross-cultural Communicative Competence: A Research-based Critical Pedagogical Model. New York, NY: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Sehlaoui, A. S. (2018a). Teaching ESL and STEM Content through CALLT: A Research- Based Interdisciplinary Critical Pedagogical Approach. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield

Sehlaoui, A. S. (2018b). Critical cross-cultural communicative competence for academic leaders. Paper presented at the Leadership in Higher Education Conference, October 18–20, 2018 Minneapolis, MN.

Stanley, C. A., Watson, K. L., Reyes, J. M., & Varela, K. S. (2018). Organizational Change and the Chief Diversity Officer: A Case Study of Institutionalizing a Diversity Plan. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000099

Taylor, L. L., Beck, M. I., Lahey, J. N., & Froyd, J. E. (2017). Reducing inequality in higher education: The link between faculty empowerment and climate and retention. Innovative Higher Education, 42(5-6), 391-405.

Wilson, J. L. (2018). A Framework for Planning Organizational Diversity: Applying Multicultural Practice in Higher Education Work Settings. Planning for HigherEducation, 46(3), 23-32.

Wolff, J., Mills, C., Fricker, M., Putnam, D., Williams, B., Angier, T., Allais, L., Metz, T., Bilchitz, D., Glaser, D., & Cudd AE. (2015). The Equal Society: Essays on Equality in Theory and Practice. Lexington Books.